If there’s one persistent buzzword in beverage marketing circles, it’s “Better-for-you.” After 100 years of being sold beverages loaded with sugar, preservatives, and artificial colorings, consumers began to become more conscious of health when making their purchasing decisions. And companies have started to take note – nearly every major supplier now ranks “better-for-you beverages” as one of their highest priorities in new product development.

But there’s something that most of these companies get wrong about this segment of the market. They think that just because consumers say they want less sugar, less alcohol, and fewer calories, that that’s what they should be given: less.

But consumers are never going to take the risk of switching to your brand if you’re giving them less. Framing this as a value add needs to be balanced with the reference point, which we can assume is usually a more tasty version of the product. After all, if you’re putting fewer calories into it, shouldn’t the price be lower too?

The breakdown comes into what psychologist Daniel Kahneman calls “System 1 vs System 2 thinking.” We all engage in both types of thinking all day long, but the processes are very different. System 2 thinking is reasoned, methodical, thoughtful – the type of logic you might make if you were asked on a survey, “What sort of beverages are you likely to purchase for you and your family in the next 60 days?”

System 1, on the other hand is immediate, reactive, and intuitive. In other words, “That soda looks tasty, so it’s going in my cart.”

So when you’re building out a new product with better-for-you in mind, ask yourself this question: how can I turn this less into more.

Here are some examples of brands that have succeeded and failed in this type of thinking:

Diet Beer

The first commercially successful low-calorie beer was introduced in 1964, and you’ve probably tasted it. You just don’t know its name.

Gablinger’s Diet Beer was introduced by Rheingold Brewery as a creation of Swiss chemist Hersch Gablinger. It used a unique patented-process for getting more alcohol out of fewer calories. But the beer wasn’t a success at first, mostly due to that one word – diet.

By the sixties, diet already had an association with worse-tasting soda. And the demographic connotations weren’t helping either – the primary market for diet soda at the time was women, which made the opportunities for capturing the then-male-focused beer audience slim. Diet beer communicated to its audience, “this beer is less tasty, and less manly.”

So after the failure of the product, Rheingold sold the recipe, and soon it ended up in the hands of a bigger supplier who had the sense to rename it – to Miller Lite.

Nowadays, light may have achieved the same connotation as diet in the American zeitgeist. But at the time, it represented the pinnacle of what major beverage makers were trying to achieve – crisp, pure, refreshing and light.

Miller Lite was everything Miller was, but more – because it was light.

Non-Alcoholic Beer

Selling non-alcoholic beer has always been a challenge, but as we’ve seen in the last five years, there’s clearly a market for it.

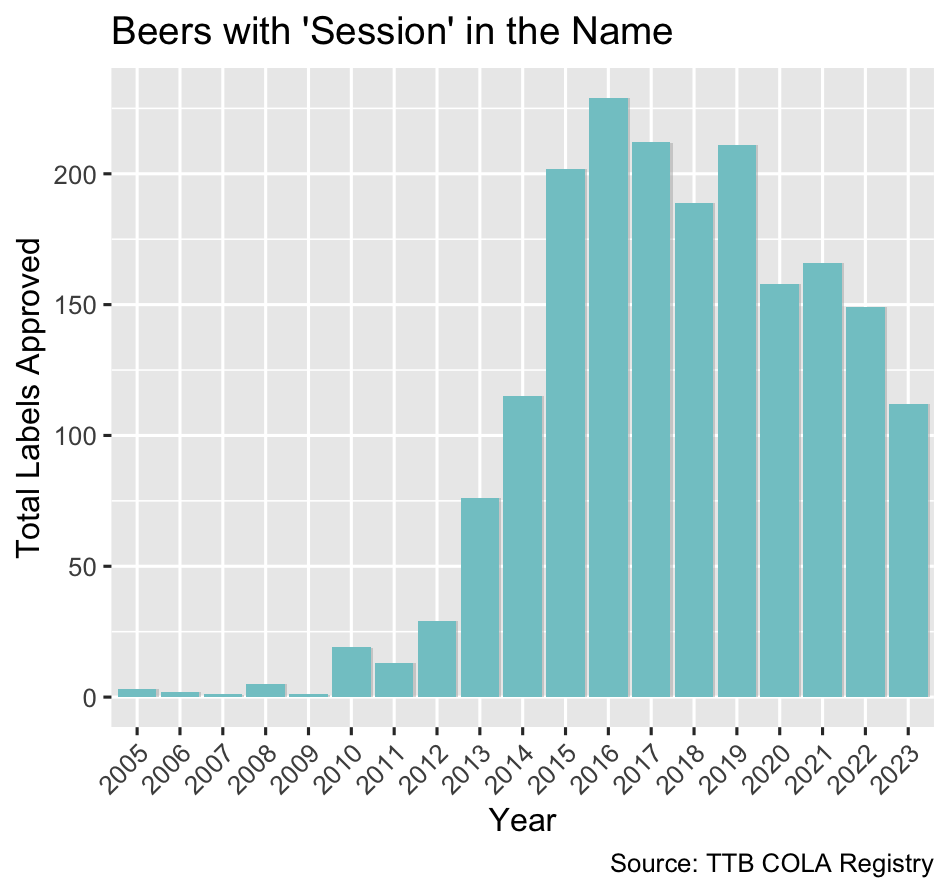

Where brands fail with this is they try to make low-alcohol sexy. For a while, craft brewers tried to market “session” as the term that showed the advantage of lower-alcohol beers – you could drink more of them!

But the term was too jargony for the public, and a poor mask for lower-alcohol, so brewers stopped trying. Federal registrations for beers with the term peaked in 2016, with 229 new packaged Session beers. Last year had less than half of that with 112.

The real winner in marketing low-alcohol, in contrast, did so by flipping the script on the value of alcohol in the product. Most of the NA brands out there have taken out just enough alcohol to be legally labeled as “non-alcoholic” – leaving them with 0.5%. Heineken, on the other hand, went all the way. In doing so, their “Heineken 0.0” implied that it was pure from nasty alcohol (a bad chemical), rather than reduced in tasty alcohol (a good chemical). In doing so, they’ve created the most popular non-alcoholic beer in the country.

Hard Seltzer

The pinnacle of the better-for-you market is inarguably the rise of hard seltzer. The bubble on that beverage may have deflated a bit since its meteoric rise in the late 2010s, but its impression was still strong enough to permanently open up a brand new segment of the market.

Why? It succeeded by not talking about what it lacked. Malt-based seltzers didn’t talk highlight what they took out of beer – calories, sugar, beer flavor. And so consumers never used beer as a reference point.

Instead, hard seltzers talked about what they added to another product – water. They were never beer-minus, they were always seltzer-plus. The ones that succeeded in this category were the ones that were seltzer-first: Truly and White Claw give impressions of clear, natural water, and the vodka-based version of High Noon associates itself with the bright cleansing sunshine of midday.

The one that failed? Budweiser Seltzer. By categorizing it with their main product they may have gotten into grocery store shelves easier, but they made it harder to get into baskets.

Liquid Death

Liquid Death clearly took a lesson from hard seltzer. But instead of adding alcohol to water, they added personality. Beer and energy-drinks are loaded with ultra-macho brands that communicate intensity as a selling point. So by positioning their product in the water category instead, they created a much bigger value-add, where that brand persona had almost no presence.

Contrast that with Hard Mountain Dew. At first glance, this product seems like it could have followed the right principles: increase the value of a known product by adding alcohol.

But in doing so, it took out two things that its consumers wanted. One was caffeine – which is understandable, as the federal government has already outlawed alcohol with added caffeine. The other was sugar, and this one just doesn’t make sense. Picture the average Mountain Dew consumer, and ask yourself this: when they see “Sugar-Free Hard Mountain Dew,” do you imagine they see that as a positive or a negative?

Olipop

Olipop is one of the fastest growing soft drinks in the market today, and they are the leader in the segment of drinks with prebiotic fibers. But although their base is clearly the more health-minded consumer, they’ve succeeded by positioning themselves as more tasty than the healthy beverages, rather than more healthy than the tasty beverages.

First, they went into grocery stores with the explicit goal of trying to take the shelf space of the over-inflated kombucha section, rather than the concentrated soda section. Kombucha has many weak brands in its segment, and so convincing buyers to lose one or two brands in favor of Olipop was an easy sell. If they had tried to enter the soda shelf, they would have faced much higher slotting fees and stiff resistance from Coke and Pepsi.

Once on those shelves, they sold their customer a brand that was aligned with the flavors of traditional soda – “Vintage Cola,” “Tropical Punch,” “Ginger Ale.” They understood that the wise, prudent buzzkill of System 2 would guide their customers to the “Healthy Drinks” section. But they also knew that once there, the impatient, rewards-driven partygoer of System 1 would grab theirs and take it home.